| STEVE H. HANKE | Steve H. HANKE |

|

CONTRIBUTING EDITOR Professor of Applied Economics at the Johns Hopkins University & Columnist at Forbes magazine |

|

Money: Bulgaria, Bosnia and Turkey |

In 1997, Bulgaria and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is commonly known as Bosnia, introduced currency board systems on July 1st and August 11th, respectively. With a currency board system, a monetary authority issues a domestic currency that is freely convertible into an anchor currency at a fixed rate. Confidence in the domestic currency is established because the monetary authority must hold foreign reserves to fully cover the domestic currency that is issued.

In 1997, Bulgaria and Bosnia and Herzegovina, which is commonly known as Bosnia, introduced currency board systems on July 1st and August 11th, respectively. With a currency board system, a monetary authority issues a domestic currency that is freely convertible into an anchor currency at a fixed rate. Confidence in the domestic currency is established because the monetary authority must hold foreign reserves to fully cover the domestic currency that is issued.

Prior to the introduction of their currency board systems, both Bulgaria and Bosnia were in bad shape. Bulgaria had defaulted on its international debt, narrowly escaped a revolution in late 1996, and was battling hyperinflation (a rate of inflation per month that exceeds 50 percent) that had virtually wiped out its banking system and sent the real economy into a free fall. It is worth noting that hyperinflations are rather rare. There have only been 30 in history, with Bulgarias 1997 hyperinflation being the last one in the twentieth century and Zimbabwes current hyperinflation being the first in this century.

The newly independent Bosnia and Herzegovina had just come out of a bloody civil war, one that had disrupted and displaced most of the population, destroyed 18 percent and damaged 60 percent of the housing stock, and covered much of the territory with land mines. Its economy was in shambles, declining to about 20 percent of its 1990 level. With the exception of the deutsche mark, the other three currencies in circulation - the Bosnia and Herzegovina dinar, the Croatian kuna, and the Yugoslav dinar - were either unstable or very unstable.

In both Bulgaria and Bosnia, I had an opportunity to play a role in designing and implementing their currency reforms. In 1991, I co-authored with Kurt SCHULER a monograph Teeth for the Bulgarian Lev: A Currency Board Solution. After its publication, I began to visit Sofia to introduce the currency board idea to government officials and the public. In particular, I can recall my meetings over the years with Todor VULCHEV who served as Governor of the Bulgarian National Bank from January 1991 to January 1996. He had studied my proposal carefully and understood it. Indeed, during our meetings, he required no staff prompting. From our first meeting until the last, Vulchevs position remained the same: We at the BNB are in full control and cant envision a scenario in which that wouldnt be the case. In consequence, we have no need for currency board rules.

These conclusions were echoed in official circles until late 1996. But, as the hyperinflation and economic collapse gathered momentum, the official resistance to the currency board idea began to crumble. What forced it to completely collapse was a sharp turn in public opinion, as well as a revolt carried out in the streets of Sofia.

The public had lost all confidence in the government and the BNB. Instead, it embraced the currency board idea. As an indicator of the publics support for the idea, consider that one of my books, Currency Boards for Developing Countries had been translated into Bulgarian and reached the top of Sofias bestseller list in early 1997.

In March 1997, President Petar STOYANOV appointed me as his economic advisor. My immediate task was to draft a currency board law and assist in implementing it. On July 1, 1997, Bulgaria introduced a currency board law to govern the BNB.

Among other things, this episode is further evidence to confirm a conclusion made by Nobel laureate Milton FRIEDMAN in his memoirs: I have long believed that we do not influence the course of events by persuading people that we are right when we make what they regard as radical proposals. Rather, we exert influence by keeping options available when something has to be done at a time of crisis.

In Bosnia, the currency board system was mandated by the Dayton/Paris Treaty (December 1995) which ended the civil war. To assist in the implementation of the new currency board system, I was invited to Sarajevo in December of 1996. And what a trip it was: military transport flights, armored cars, body guards and other local oddities.

At the time of their installation, critics claimed that neither currency board would succeed because Bulgaria and Bosnia didnt meet preconditions required for a successful currency reform. Those who peddle this precondition notion claim that a currency board is unlikely to be successful without solid economic fundamentals, adequate reserves, fiscal discipline, a strong and well-managed financial system and an adherence to the rule of law.

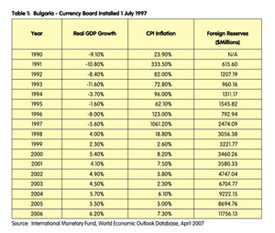

The preconditions argument falls into what I term the 95 % Rule: ninety-five percent of what is written about economics is either wrong or irrelevant. Just look at Tables 1 and 2. In the last decade, Bulgaria and Bosnia have experienced sustained economic growth, stable prices and a rapid increase in the demand for the currencies produced by their currency board systems (as reflected in the growth in foreign reserves).

Since long before writing Gelişmekte Olan Ülkeler İçin Para Kurulları El Kitabı in 2001, it has been clear to me that Turkeys economy would be in better shape today if it had followed the sound money path taken by Bulgaria and Bosnia. The facts contained in Table 3 support this conclusion.