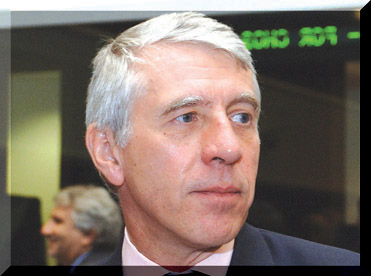

| JACK STRAW | UK Foreign Secretary |

|

Bridging The Bosphorus-Turkey's European Future |

I had many emotions that sombre evening, but one was of the powerful, reassuring, uncompromising solidarity that I’d been offered by the Turkish government and people; the other of how familiar, yes European, Istanbul felt; how close we were together, despite the efforts of the terrorists to divide us.

I had many emotions that sombre evening, but one was of the powerful, reassuring, uncompromising solidarity that I’d been offered by the Turkish government and people; the other of how familiar, yes European, Istanbul felt; how close we were together, despite the efforts of the terrorists to divide us.I've often had flash-backs to that day and how I felt as we have discussed Turkey's long-standing application to join the European Union. These talks are now entering what could be their crucial final phase before the 3rd October date set for the start of negotiations towards full membership of the Union. It is therefore worth underlining Turkey's strategic importance, and the momentous consequences which will follow from that event.

Of course, the land which is now Turkey has been a part of European history for centuries. The great armies of Darius and Xerxes were ferried across the Hellespont in one direction; Alexander the Great and his army in the other. Turkey still bears the marks of the Greek, Roman and Byzantine civilisations which have done so much to shape modern Europe. And for 1000 years after the fall of Rome, Constantinople was one of the world’s two great centres of Christendom.

Throughout the 18th, 19th and early 20th century policy towards the Ottoman empire – the so-called Eastern Question – preoccupied the great European powers. In the 1850s it led to Britain and France fighting the Crimean war together against Russia and alongside Turkey. The Turkish republic, which was founded in October 1923, saw its future firmly faced the West. Its founder, Kemal Ataturk, laid the foundations for the democracy which Turkey now is. He was responsible for the introduction of the Latin script. And in 1934 he gave women the vote – years before many Western European states did so. I could name them – but I won’t. In any case, it was only six years after the UK had given women the vote.

Turkey’s engagement with the West – and vice-versa – has carried on unbroken into post-war history. Turkey was a founding member of the Council of Europe. With the agreement of the US, UK, France and others, Turkey was invited to join the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation in 1952. It’s worth spelling the acronym out in full. What we were doing was inviting Turkey into NATO – I hope for their own benefit – but also for ours to help defend the North Atlantic area.

Throughout the cold war Turkey was one of only two NATO countries that shared a border with Soviet Union and has continued to play a part in collective defence and peacekeeping operations right up to the present day – most notably in Afghanistan Turkey’s relations with the European Union – then the EEC – began in 1963 with the signing of an association agreement establishing a customs union in three stages. It is significant that at the signing ceremony that day, Walter Hallstein, the German Christian Democrat and the first President of the European Commission, referred three times to Turkey being part of Europe. The association agreement held open the possibility one day of Turkish membership; and in 1987 Turkey applied to join the Union. In 1999, she was granted candidate country status and in 2002 the European Council formally decided in Copenhagen that it would open accession negotiations without delay, once Turkey had fulfilled the political criteria for membership. Of course, all these decisions were, and had to be, unanimous.

The history of all this is important. It clearly demonstrates that the destinies of Turkey and the rest of Europe have long been intertwined. It also shows that when the European Council made its historic decision at the end of last year to set the date for the opening of accession negotiations – October 3 – it was the latest step in a long journey.

There is more at stake here than Turkey’s future. This is about Europe’s future too. And it is a question of paramount importance for the whole international community. Turkey is a secular nation with a majority Muslim population. By welcoming Turkey we will demonstrate that Western and Islamic cultures can thrive together as partners in the modern world. The alternative is too terrible to contemplate. This is the strategic importance of the step Europe will take next month. The European Union has already demonstrated its power to heal division in the most practical way by welcoming countries who were long divided from us by the iron curtain. We now have the opportunity to achieve something as profoundly important by starting Turkey on the road to full EU membership.

In my 1950's schooldays I was taught that the formal boundary between Europe and Asia went straight down the Bosphorus through the middle of Istanbul, putting Turkey’s former capital in both continents. But the truth is that Europe – in the wider historical sense – defies any simple definition. In 1876, Bismarck scribbled on the back of a telegram: "Anyone who speaks of Europe is wrong – it is nothing but a geographical expression". Seventy years later, Jean Monnet, ‘the father of Europe’ echoed those words: "Europe has never existed – one has genuinely to create Europe".

So the decisions on Turkey made by the European Council over many years have been decisions about the kind of Europe which we want to create. Is it a Europe turned inwards on itself or a Europe looking outwards to the rest of the world; how much will we expand our boundaries to build a wider community of stable, prosperous democracies or how much will we keep our neighbours at arms length?

We live in a world of global challenges and global competition. A static Europe will not face either with confidence. No-one is arguing that Europe has no limits. But stopping the enlargement already in train would not, in the long run, save one job nor keep one firm in business. Rather we judge that it would only weaken Europe’s ability to compete with the emerging economies of Asia – and in particular those of India and China. Neither would slowing enlargement help us to tackle the challenges of international terrorism, cross-border crime, drug trafficking and climate change.

For we should all be clear about one thing. Enlargement has been good for the new member states who’ve joined and it has been good for the European Union. As Spain, Portugal and Greece threw off one-party rule and began to entrench democratic institutions during the 1970s, the prospect of EU membership acted as a powerful motor for change. In the 1990s, as the countries of Eastern Europe emerged from the shadow of communism, the EU again drove a similar process. The goal of EU membership gave those countries a powerful incentive for both political and economic reform, as they opened their economies to trade and implemented EU laws and standards.

This enlargement over the last two decades has not diluted the stability and prosperity of the then current members states – rather it has enhanced it. It has peacefully united much of Europe after generations of division and conflict. It has incorporated the young and growing economies of Eastern Europe into the largest single market in the world. And it has increased the influence of the EU internationally. At a time when the European Union does indeed have to reconnect to its citizens and show them the concrete benefits of the EU, we should proudly display enlargement as one of its greatest success stories. Every acceding country admitted to membership has had to meet strict criteria, especially on good governance, democracy, individual freedoms, and economic management. But we should remember that when some of the new member states – including recent accession states – began their negotiations they were a long way short of the standards for membership itself.

They transformed during that process of negotiation– and because of that process – just as Turkey will go through a major, continuing process of transformation over a number of years before it joins the Union. We should have confidence in Commission officials and successive Commissioners, including Olli Rehn and his predecessor Gunther Verheugen, to ensure that accession negotiations are rigorous and scrupulous; and we do. So why Turkey and why start now? Turkey’s geographical position makes it of vital strategic importance in every way. I could give many examples. Take the fight against drug trafficking, cross-border crime and international terrorism. Take the issue of energy. The Bosphorus is already a key supply route for the world’s energy needs. And once the Azerbaijan to Turkey pipeline begins to pump one million barrels per day through Turkey later this year, 10 per cent of the world’s tradeable oil production will be passing through Turkey.

Turkey’s economy is growing faster than any of the current economies of the European Union. Half of Turkey’s trade is already with the EU and it is already a major market for EU exporters. And again, of course, we shouldn’t forget that if and when Turkey does become a member, as I said, it will be after years of structural reforms and with a long track record of sustained and stable growth.

The political rationale behind Turkish membership is even more powerful. I have spoken already of the terrorists’ desire to turn Turkey away from Europe. They know that in a world where some want to see clash of civilisations, Turkish accession would show instead how diversity of culture and religion is compatible with a unity of purpose.

We can already see this within the European Union’s current boundaries. Our largely Christian heritage is overlaid by successive layers of reformation and counter-reformation, of secular enlightenment and of the influx of new religions. Today several of the countries of the European Union count over a million Muslim citizens each. In the United Kingdom the figure is closer to two million. A stable, prosperous Turkey anchored in the European Union would be a powerful symbol indeed that the true divide lies not between civilisations but between the vast majority of civilised people across the world and the uncivilised few who use violence and terror to try to destroy the common values and beliefs which bind the rest of us.

It will prove that a secular, democratic state which shows respect for Islam can live comfortably within Europe. Conversely, what message would we give out if we were perceived to turn away from Turkey? The benefit that Turkey can offer to our security is already plain; only last week it was Turkey which brokered the historic meeting between the foreign ministers of Israel and one of the Islamic countries of the world – Pakistan.

So my third question is why start now? As I said earlier, Turkey’s vocation in the EU was recognised as long ago as 1963. The prospect of EU membership, particularly over the last four years, has driven an impressive process of change in Turkey. Prime Minister Erdogan’s AKP government has pursued a wide-ranging and courageous programme of reform. There is still some way to go with implementation, as the recent charges against the distinguished Turkish novelist Orhan Pamuk show, in the context of freedom of speech. But the progress has been dramatic. The death penalty has been abolished. Taboos have been broken on Kurdish issues. Mindsets are changing. Turkey is now a great deal closer than it was to European standards, as the European Council itself has recognised.

In December the European Council decided that Turkey had sufficiently met the Copenhagen political criteria to begin negotiations on October 3rd. But the council set two strict conditions before those negotiations could begin. Turkey was asked to enact six pieces of legislation which would reinforce the rule of law and human rights in that country. They did this on 1 June. Turkey was also asked to sign a protocol to the EU-Turkey Association Agreement expanding that 1963 agreement and following enlargement. This Turkey did on 29 July. As for any accession state there is still much to do before Turkey will have met the conditions necessary actually to join the Union.

There are thirty-five separate chapters which will have to be opened and closed during accession negotiations. These cover issues from justice and home affairs through to economics and the environment. Meeting the standard on all these chapters will require the continued and sustained commitment from the Turkish government. And the result of any accession negotiations – by their very nature – cannot be prejudged.

It is clearly right, however, that the European Union should now follow through on its decision to begin negotiations; negotiations which, under the watchful eye of the Commission, we expect to be long and complex and involve the continuation of reform. To do otherwise would not only compromise the credibility of the EU but might also endanger the considerable progress already made in Turkey. We should be very clear indeed about what is at stake. We all have an interest in the modernisation of Turkey, and of reform there. If we make the wrong decisions we could find that we have a crisis on our own doorstep.

That then is the big picture – the strategic imperative for Turkey to move towards membership of the European Union. Turkey’s nearest neighbours in the EU – Greece and Cyprus – have been among the strongest supporters of this strategic imperative. And Turkey’s progress towards membership is clearly in the interests of that region – a region still bedevilled by unresolved disputes – including those over Cyprus and over the Aegean.

I would have preferred it if the Government of Turkey had not felt it necessary to issue its declaration stating that its signature of the Association Agreement Protocol did not amount to recognition of the Republic of Cyprus. By doing so the process has frankly been made more difficult. The European Union is discussing how to respond and will do so appropriately. Our common goal is to ensure that the Customs Union between Turkey and all 25 EU member states – including Cyprus – is implemented fully and without discrimination.

But acknowledging that Turkey’s declaration raises genuine concerns – which we, as Presidency, are working hard to address - does not mean that we should delay the start of Turkey’s historic accession negotiations. We should have faith in the power of the Union to help resolve problems.

Our own experience in the UK suggests that the engagement within the European Union can help to resolve the most difficult of disputes. When the UK and the Republic of Ireland joined the then European Economic Community in 1973, there was still a very significant and unresolved argument about the sovereignty of part of the territory of the UK. Ireland, by its own constitution, lay claim to Northern Ireland – part of the UK. I cannot prove that EU membership resolved our differences with Ireland over their claim to Northern Ireland. But I do believe that the shared prosperity from the EU, the very much closer commercial and economic ties and the very fact of regular political contact on mundane, daily business of the Union at the very least made the peace process 25 years later much easier and in many ways imperative.

But I actually think that historians of the future will give more credit to the joint membership of the EU in resolving this significant territorial dispute. And while the people of Ireland showed impeccable behaviour during the entry of Ireland into the EU, we should not forget the bloody backdrop to our joint accession in 1973. Terrorists were carrying out atrocities both in Northern Ireland and on the mainland of Britain. This was hardly a propitious beginning. But the territorial dispute has since been resolved.

And while we are on the topic, it is public knowledge that Spain and the United Kingdom have a difference of emphasis over Gibraltar. This steps from the 1713 Treaty of Utrecht and from Article 10 in particular. The Article says that we can have it but if we give it up it goes to Spain. I paraphrase. This has caused lots of problems – particularly for the people of Gibraltar. But I hope a resolution will be found and if and when it is, I believe that it will stem from our joint membership of the EU. I want Cyprus – Turkish Cypriots and Greek Cypriots alike - to reap the same benefit. This is not a new approach that the UK is taking. Faith in the EU’s healing power, was one reason why in 1997 we took the lead in arguing that the absence of settlement in Cyprus should not be a barrier to the Republic of Cyprus joining the EU. This was confirmed by the European Union in 1999.

We should keep this faith, by allowing Turkey’s accession process to go ahead and – the other key ingredient – by helping the parties in Cyprus to re-invigorate their UN-sponsored search for a settlement under the good offices of the UN Secretary General and under the authority of a number of UN Security Council Resolutions. The European Union faces a moment, the importance of which we must not underestimate. It will shape the future of the world in which we live. It is one upon which stands the security and prosperity of Europe itself. We cannot afford to get this wrong.

Turkey-Eu Accession Talks Agreement 'A Truly Historic Day For Europe'

This is a truly historic day for Europe and for the whole of the international community. It’s now more than forty years since the prospect of membership of the European Union was first held out to Turkey. It was a prospect that was repeated in 1999, in 2002, in December last year and again in June of this year. Given the time that it’s taken it’s perhaps no surprise that these negotiations to begin formally the negotiations should have taken more than twenty four hours to finalise the agreement that we have just reached inside the Foreign Ministers’ Council.

I’d like to thank all my colleagues for the patience and forbearance that they have shown. It, this has been a, a collective effort with twenty five colleagues in the room with the Government of Turkey, and all colleagues in the Government of Turkey have shown great statesmanship recognising that the prize is such an important one. I’d particularly like to thank, if I may, Olli REHN the Commissioner for Enlargement and all of his staff, Javier SOLANA the High Representative and Secretary General of the Council and all of his staff, and too if I am allowed to I’d like to thank Sir John GRANT of the United Kingdom’s Permanent Representative and all the presidency staff from the United Kingdom Diplomatic Service for the great job, fantastic job which they have been able to do.

Every enlargement that has taken place within the European Union has made both the existing and the new member states stronger and more prosperous. I’m in absolutely no doubt that these benefits will follow from this enlargement and it will bring a strong secular state which happens to have a Muslim majority in to the European Union. Proof that we can live, work and prosper together and we are all much stronger for being united than for, for being divided.

Now as everybody knows this is the start of the negotiation process far from its finish. It’s going to be a long road ahead but I’m in no doubt that bringing Turkey in to the European Union is a prize worth striving for and if the sentiment that has been around today, positive sentiment of co-operation continues which I think it will do then I think the, the future is good. This is a negotiation in which we are all winners: Europe, the existing member states, Turkey, and the international community. Allow me now just to move on to the issue of Croatia because I believe that this is also going to be a good day for Croatia as well.

Carla del PONTE the Chief Prosecutor for the International Criminal Tribunal in The Hague today reported that Croatia is now fully co-operating with her tribunal and its staff. There is currently a meeting of the Croatia Task Force taking place now. I don’t want to anticipate the formal outcome of that meeting but I hope that there will be a good and positive result from that as well. And obviously we’ll keep you up to date as soon as possible.